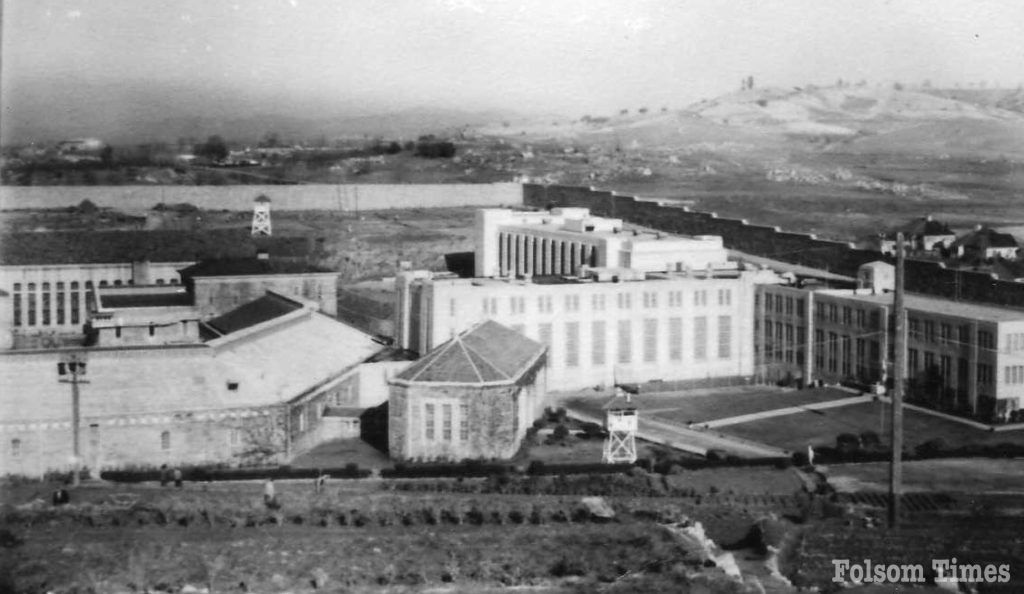

On this day in 1880, 44 men stepped off a train in Folsom and entered what would become one of the most storied and scrutinized institutions in California history. Today, July 26, marks the 144th anniversary of the opening of Folsom State Prison — California’s second oldest correctional facility and one of the nation’s first maximum-security prisons.

While its granite walls have stood witness to hardship, violence, and infamy, they have also borne silent testimony to innovation, rehabilitation, and a curious kind of resilience.

A Prison Born of Overcrowding and Industry

The road to Folsom’s opening was anything but swift. In 1858, the California Legislature responded to overcrowding at San Quentin by authorizing a second prison. But it would take a full 20 years before the first inmates arrived by train from Sacramento after making the journey upriver by boat from San Quentin. Originally envisioned as a branch of San Quentin, Folsom State Prison became fully operational in July 1880, with a population that had grown to 900 by 1897.

Though the prison was nearly constructed in Rocklin, H.P. Livermore of the Natoma Land and Mining Company offered the state land in Folsom in exchange for the use of prison labor — a decision that sealed the prison’s permanent home. The location was ideal not just for containment — with the American River forming a natural barrier — but also for industrial progress. That same river would later power the first hydroelectric plant in the Sacramento region.

Inmate labor helped build the prison’s early infrastructure, including its dam, canal, and later, the prison’s very own powerhouse. The canal system also became a point of contention in the 1890s as logs floated downriver to power local sawmills. Logging magnate Horatio Gates Livermore envisioned Folsom as a regional industrial hub and sought to use the prison canal for timber transport.

Though prison officials initially resisted adjusting the gates due to power concerns, the sawmill opened in 1896 and could cut up to 75,000 board feet of lumber per day — an electrified industrial marvel of its time. Heavy rains and high river levels eventually forced 3 million feet of logs over the dam, shuttering the mill in 1899, but the impact on Folsom’s economy was lasting.

No Walls, No Escape — At First

When Folsom State Prison opened, it had no towering granite walls. Instead, towers dotted the property, offering clear views of the inmates working outdoors. The cells themselves were encased in thick iron, stacked within another building to prevent access to exterior walls. They lacked plumbing or heat, and lighting came from oil lamps — a grim setup that reflected the harsh conditions for which Folsom would become known. Each 8-by-7-foot cell featured a solid iron door with a narrow 8-inch by 2-inch viewing slot and six drilled ventilation holes. There were no toilets, no running water, and very little comfort.

Escape attempts began almost immediately. Critics pushed for permanent barriers. It wasn’t until 1909 that construction began on the now-iconic granite walls, completed in 1923. Even before that, the facility had earned its nickname as “the end of the line” — reserved for habitual criminals and those serving long sentences. That same year, the prison purchased a steam locomotive, Southern Pacific engine No. 2083, for $4,850 to support transport and quarry operations — a testament to the prison’s self-contained industrial scale.

Innovation Inside the Walls

Despite its austere reputation, Folsom was no stranger to innovation. By 1893, it became the first prison in the United States to have electric lights — a feature that came from its own power generation efforts. That same year, the prison launched an ice plant that would become the first of many industries to operate behind its walls. So successful was the venture that the state legislature funded expansion, linking the prison’s ice with the rise of California’s fruit shipping industry.

The prison’s Power House, completed in 1891, became a hub of industry. Logs from upriver were funneled down a canal system to power sawmills. A prison-run rock crushing plant also opened in 1895, supplying building materials throughout the region.

In 1930, another lasting industry began: license plate manufacturing. The California Prison Authority’s factory at Folsom produces every license plate for the state, with approximately 50,000 plates made daily — a legacy that continues to this day.

The Man Behind the Reform

Perhaps the most transformative figure in the early history of Folsom Prison was Warden Charles Aull. Appointed in 1887, Aull brought structure and humanity to an otherwise unrelenting institution. Though known for strict discipline, Aull also introduced recreation programs for inmates — including baseball games that became weekend traditions. His leadership was so respected thatThe San Francisco Callonce called Folsom “a model institution” under his watch.

Aull’s contributions were cut short when he fell ill and died in 1899, but his impact on prison reform and structure endures in the historical record. He is credited with striking a balance between discipline and dignity, at a time when few correctional leaders prioritized either.

Recreational opportunities expanded further over the decades, with organized baseball competitions held from 1915 to 1965. Some of the biggest names in baseball — including Joe DiMaggio, Ernie Lombardi, and Stan Hack — visited the prison to play exhibition games. Fourth of July events, beginning in 1893, became major celebrations featuring Vaudeville-style inmate productions, stage plays, and tug-of-war contests, often officiated by prison staff. One inmate even painted a rendition ofThe Last Supperinside Greystone Chapel in the 1930s, completing it just before the start of World War II.

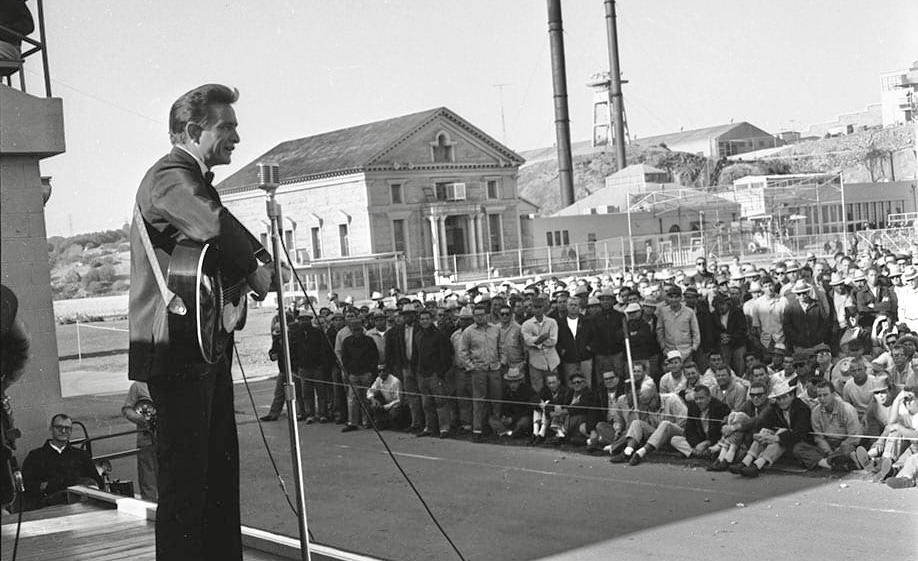

A Legendary Day: Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison

Folsom State Prison gained international fame on January 13, 1968, when legendary country artist Johnny Cash recorded his now-iconicAt Folsom Prisonlive album inside its walls. Though Cash never served time himself, he was deeply empathetic toward the incarcerated, inspired by the stories of the downtrodden and forgotten. That empathy took root with his 1953 composition “Folsom Prison Blues,” written while Cash was serving in the U.S. Air Force in Germany. Inspired by the 1951 filmInside the Walls of Folsom Prison, the song became one of Cash’s most recognizable hits, punctuated by its dark lyric:“I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.”

Cash had actually performed at Folsom once before in 1966, though that show was not recorded. When producer Bob Johnstone finally greenlit a live prison recording, Folsom was the first to say yes. On January 13, 1968, Cash took the stage for two performances, backed by The Tennessee Three, Carl Perkins, The Statler Brothers, and June Carter. They closed the sets with “Greystone Chapel,” a song penned by inmate Glen Sherley and shared with Cash just the day before by prison chaplain Rev. Floyd Gressett.

The final album was released in May 1968 and shot to the top of the charts. “Folsom Prison Blues” hit No. 1 on the country charts and cracked the Billboard Hot 100, eventually earning Cash two GRAMMY® Awards. Though radio stations briefly pulled the song after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy due to its controversial lyrics, the reissued single — minus one infamous line — still became a classic. Cash would later go on to record other prison albums, but none left a mark like Folsom.

Breakouts and Bloodshed: Early Escapes

With a history spanning nearly a century and a half, Folsom State Prison has witnessed more than its share of violence and escape attempts. One of the earliest and most infamous occurred in 1903, when 13 inmates armed with knives broke from a mess hall line, killing a guard as they fled. Six were recaptured, one was killed, and six were never seen again.

Another violent episode unfolded in 1937 when several inmates, armed with knives and wooden Tommy guns, attempted another breakout. Two inmates were killed during the chaos, as well as a guard and the prison warden. Five of the perpetrators were later convicted and became the first inmates executed in San Quentin’s gas chamber. In earlier years, escape-prone inmates were forced to wear red shirts to mark them as high risk.

A Centerpiece of Folsom’s Identity

Folsom Prison’s legacy stretches far beyond incarceration. The site played a role in California’s industrial rise, provided early electricity to the region, and stood as a cultural touchstone for more than a century — from its role in shaping corrections philosophy to serving as the stage for one of the most memorable moments in music history.

The prison also briefly housed women — six in total — though none have been incarcerated there since 1929. On November 7, 1885, the first female inmate arrived, but the facility was never considered suitable for long-term female incarceration. Greystone Chapel, completed in 1903, still stands as a spiritual and architectural landmark inside the prison.

In 1907, the state began construction of a hospital for the criminally insane within the prison grounds. Built with granite by convict labor, the structure was used briefly to house low-level inmates. Though the facility was never completed as intended, it stood for decades before being demolished in the 1950s, offering a reminder of the evolving — and sometimes abandoned — ideas in criminal justice.

Today, Folsom State Prison primarily houses medium-security inmates and offers educational and vocational programs through Greystone Adult School. A minimum-security facility operates just outside its main perimeter, continuing the tradition of structured rehabilitation and training.

From Granite to Legacy

Folsom State Prison has come a long way since its early days as a prison without walls. It has grown from a site of harsh confinement into a symbol of reform, innovation, and history — still active, still relevant, and still looming large over the American imagination.

As it enters its 145th year, Folsom Prison remains both a landmark and a reminder — of how far the state has come in its criminal justice journey, and how much of that story was carved right here in the granite of Folsom.

Special thanks to the California Departmenr of Corrections, the Library of Congress, Folsom History, and the City of Folsom for their assistance and materials in this article.

Copyright © 2025, Folsom Times, a digital product of All Town Media LLC. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.